The Great Fall "Migration"

A family cruise through the Eastern Caribbean, blending birding, family time, and FeatherQuest stories

- St. Croix — the moment the quest finally started

- Magnificent Frigatebirds at eye-level from a few decks up

- Puerto Rico — El Yunque humidity, fogged gear, and the jungle winning (until a Grackle saved the day)

- CocoCay — beach birds, familiar shorebird energy, and a calmer rhythm to end on

- Ruddy Turnstone

- Scaly-naped Pigeon

- Greater Antillean Grackle

- Northern Parula

Eastern Caribbean Cruise

Oct 17–25, 2025When I look back on this trip now, the thing that surprises me most is how you can both have an amazing family vacation and still complete a few successful birding quests.

This was always going to be a family-first trip. Fall break. A cruise. Built-in schedules, short windows, and long stretches where birding simply wasn’t the point. Still, I was on—scanning railings, checking treetops, watching shorelines slide past while everyone else relaxed into vacation mode.

My wife and daughters even did a little birding of their own. They love “duck hunting” on cruise ships—the planted toy ducks people hide everywhere. Different targets, same instinct. Look closely. Keep your eyes open. See what turns up.

St. Croix — Where the Quest Woke Up

Finally we arrived at St. Croix, and it was time to get out there.

There was room to wander. Fewer crowds. Less clock-watching. It felt like the trip finally exhaled, and the birds did too. This was the moment when birding stopped being something I was squeezing in and started feeling possible again.

Birds appeared without urgency. Time slowed just enough to notice behavior, posture, light. It wasn’t a flood of species—it didn’t need to be. It was simply the confirmation that the quest was alive.

As we headed back toward the ship, Magnificent Frigatebirds started circling overhead like they owned the sky. From the dock they were the usual story—high, distant, untouchable. But on a cruise ship you get one unfair advantage: height. I climbed up a few decks and suddenly they weren’t dots anymore. They were eye-level—close enough to notice the color on their faces and the way they barely seemed to flap, just steering the wind like it was solid.

The next day, St. Thomas slowed everything back down. We leaned into a proper beach day, watched massive green iguanas sun themselves like they had nowhere else to be, and let the camera rest more than it worked. I made a single photo on the walk back to the ship—nothing rare, nothing urgent—and that felt right. Not every stop needs to push the quest forward. Some just remind you to notice what’s already there.

St. Croix Gallery

Puerto Rico — When the Jungle Wins

Puerto Rico should have been great on paper.

We hiked into lush forest. The habitat was right. The expectations were high. But the birds stayed deep, the rain came hard, and the focus stayed on the hike. Add Caribbean humidity and camera gear still trying to acclimate, and the whole thing felt slippery and unsettled.

This is one of the hardest lessons for early travel photographers: in hot, humid places, your gear struggles before you do. Fogged glass. Fogged viewfinders. That quiet panic of wondering whether the moment is already gone.

It almost was.

A Greater Antillean Grackle ended up being the small save. Not dramatic. Not flashy. Just present. Enough to remind me that even when a place doesn’t open the way you hoped, it’s still giving you something—if you’re paying attention.

The Bird That Kept Coming Back

The Ruddy Turnstone first showed up in St. Croix.

It was a lifer, and the adrenaline hit exactly as expected. Heart rate up. Shots taken fast. The moment felt big and brief all at once.

Then, days later, at CocoCay, it happened again.

Same bird. Same posture. Different me.

When you get a second chance at a bird you just added, everything changes. The urgency drops. The seeing improves. You start noticing angles instead of just evidence.

Both encounters mattered. They produced different images for different reasons. But the second one stayed longer.

It’s funny how that works. You don’t see a bird for years. Then you see it once—and suddenly it keeps finding you.

CocoCay — The Easy Yes

For birding on a cruise, CocoCay almost always works.

It’s walkable. Unrushed. Built for wandering. Birds and people share the space without much concern for one another.

A White Ibis strolled straight through crowds eating lunch, bold enough that getting a clean angle became the challenge. I was too close. There were always people in the way. A good problem to have.

A hummingbird tried feeding from a bright pink piece of clothing in a shop—clearly unimpressed with the lack of nectar but committed to the attempt.

And then there were the gulls.

Laughing Gulls. American Herring Gulls. Lesser Black-backed Gulls. Side by side, close enough to slow down and really look. Gulls are endlessly intriguing—everywhere in the world, deceptively similar, and deeply humbling once you start paying attention. I left knowing I still have a lot to learn.

CocoCay Gallery

After the Trip, Still Learning

Even after we were home, the trip wasn’t finished teaching me.

Photo review has a way of extending a journey. Slowing it down. Letting details surface that didn’t announce themselves in real time. That’s when a quiet lifer revealed itself: a Northern Parula, easy to miss in the moment, unmistakable once the pace changed.

Another reminder that photos aren’t just trophies. They’re memory extensions.

Leaving Something Behind

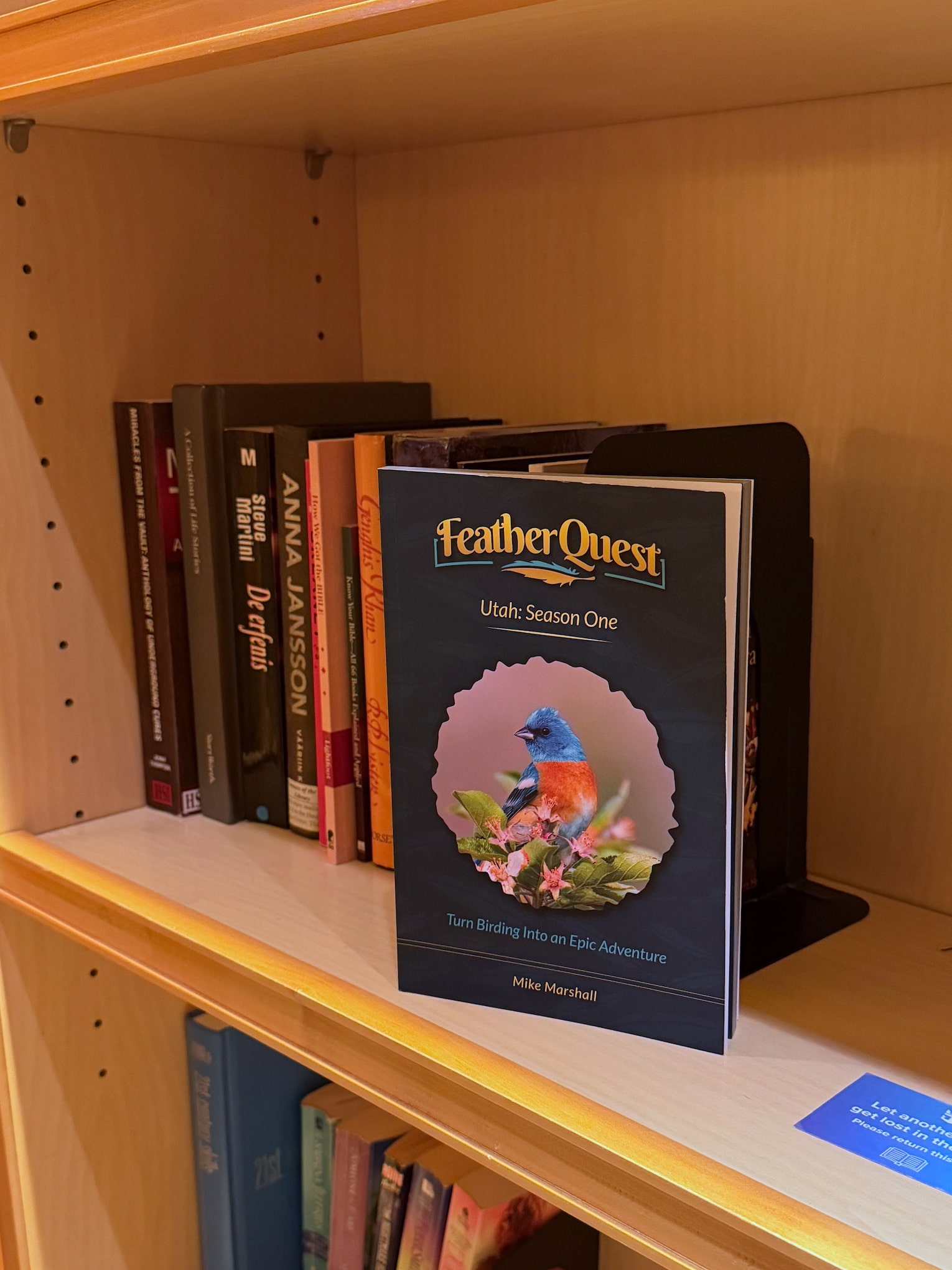

When I travel now, I always bring two copies of FeatherQuest. One is mine. The other is meant to find its own path.

On this trip, I finally left one behind.

I signed it. Dated it. Then placed it in the ship’s library.

I don’t know who will pick it up. Or when. Or what it might spark. But I like the idea that while I was learning more about my own trip through photos and reflection, someone else might stumble into their own adventure the same way.

Birding in uncharted waters always leads to something exciting.